Nearly 25% of Americans are functionally unemployed, struggling to find work despite the seemingly positive official unemployment rate, highlighting a significant disconnect between government statistics and the reality faced by millions. This “hidden unemployment” encompasses those marginally attached to the workforce, working part-time for economic reasons, or discouraged workers who have given up actively seeking employment, painting a more comprehensive and concerning picture of the nation’s labor market.

The official unemployment rate often touted as a key indicator of economic health, fails to capture the full scope of the employment struggles faced by a substantial portion of the population. According to a recent analysis, nearly one in four Americans are grappling with employment challenges that extend beyond the standard definition of unemployment. This hidden unemployment manifests in several forms, including individuals who are marginally attached to the workforce, those forced to work part-time due to a lack of full-time opportunities, and discouraged workers who have ceased their job search altogether. This underutilization of labor resources points to deeper systemic issues within the economy that require a more nuanced understanding and targeted policy interventions. The situation suggests a significant undercurrent of economic insecurity that is not fully reflected in the headline figures.

“The headline unemployment number is, in our view, highly misleading,” said Julia Pollak, chief economist at ZipRecruiter, emphasizing the limitations of relying solely on the official unemployment rate. “The labor market is not nearly as strong as the 3.9% headline unemployment rate suggests.” This sentiment is echoed by labor market analysts and economists who argue that a more holistic view of employment is necessary to accurately assess the economic well-being of the population. The discrepancy between the official rate and the experiences of a quarter of the American population underscores the need for policymakers and the public to consider a broader range of indicators when evaluating the health of the labor market.

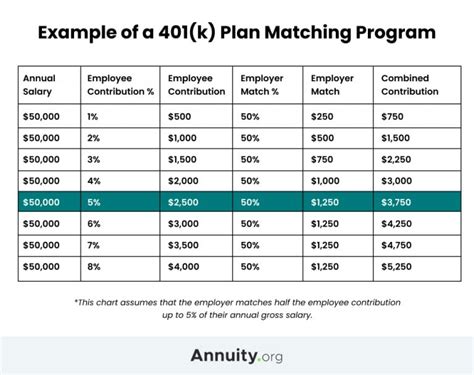

The U-6 unemployment rate, a broader measure that includes marginally attached workers and those employed part-time for economic reasons, offers a more revealing perspective. This rate consistently runs higher than the headline unemployment rate, reflecting the hidden challenges within the labor market. Many individuals classified as “part-time for economic reasons” would prefer full-time employment but are unable to secure it due to business conditions or lack of available positions. Similarly, marginally attached workers are those who are able and willing to work but have not actively searched for a job in the past four weeks, often due to discouragement or family responsibilities.

The consequences of this hidden unemployment are far-reaching, impacting individual financial stability, household incomes, and overall economic growth. Individuals struggling to find stable, full-time employment may face difficulties meeting basic needs, accumulating savings, and planning for the future. This can lead to increased stress, anxiety, and mental health challenges. Moreover, the underutilization of labor resources represents a loss of potential productivity and economic output for the nation as a whole. Addressing the issue of hidden unemployment requires a comprehensive approach that includes policies aimed at creating more full-time job opportunities, providing job training and skills development programs, and supporting workers facing barriers to employment.

The current economic climate, characterized by rapid technological advancements, evolving industry demands, and lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, has exacerbated the challenges faced by many job seekers. Automation and artificial intelligence are transforming the nature of work, requiring individuals to adapt to new skills and competencies. The pandemic led to widespread job losses, particularly in sectors such as hospitality, retail, and tourism, and while some industries have recovered, others continue to struggle. These factors contribute to the pool of hidden unemployed, making it more difficult for them to re-enter the workforce and achieve economic security.

Moreover, the rise of the gig economy has created both opportunities and challenges for workers. While gig work offers flexibility and autonomy, it often lacks the benefits and protections associated with traditional employment, such as health insurance, paid time off, and retirement contributions. Many gig workers are classified as independent contractors, which means they are not eligible for unemployment insurance or other social safety net programs. This can leave them vulnerable to economic insecurity, especially during times of economic downturn or personal hardship.

Addressing the issue of hidden unemployment requires a multi-faceted approach that tackles both the supply and demand sides of the labor market. On the supply side, policies should focus on providing individuals with the skills and training they need to succeed in the modern economy. This includes investing in education, vocational training, and apprenticeship programs. It also involves addressing barriers to employment, such as lack of access to affordable childcare, transportation, and healthcare.

On the demand side, policies should aim to create more full-time job opportunities and promote inclusive economic growth. This includes investing in infrastructure projects, supporting small businesses, and encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship. It also involves addressing issues such as wage stagnation, income inequality, and workplace discrimination. By creating a more equitable and inclusive labor market, policymakers can help reduce hidden unemployment and ensure that all Americans have the opportunity to achieve economic security.

The findings highlight the limitations of relying solely on the headline unemployment rate as an indicator of economic well-being. While the official rate may suggest a healthy labor market, the reality for millions of Americans is far more challenging. By recognizing and addressing the issue of hidden unemployment, policymakers can create a more inclusive and equitable economy that benefits all members of society. The need for a more comprehensive approach to measuring and addressing unemployment is evident, urging for policies that reflect the complex realities of today’s labor market and support the economic well-being of all Americans.

In-Depth Analysis:

The assertion that the “headline unemployment number is…highly misleading” prompts a deeper examination of the metrics used to assess employment and economic health. The official unemployment rate, typically referred to as U-3, measures the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed and actively seeking work. The labor force consists of individuals aged 16 and older who are either employed or actively looking for employment. Individuals who are not actively seeking work, whether due to discouragement, family responsibilities, or other reasons, are not counted as part of the labor force and are therefore not included in the unemployment rate.

This narrow definition of unemployment fails to capture the experiences of a significant portion of the population who are struggling to find adequate employment. These individuals may be marginally attached to the workforce, working part-time for economic reasons, or discouraged workers who have given up their job search. Each of these categories represents a distinct form of underutilization of labor resources.

Marginally attached workers are those who are able and willing to work but have not actively searched for a job in the past four weeks. They may have stopped searching due to discouragement, lack of available job opportunities, or family responsibilities. These individuals are not counted as unemployed because they are not actively seeking work, but they represent a potential source of labor that is not being fully utilized.

Individuals working part-time for economic reasons are those who would prefer to work full-time but are unable to find full-time employment. They may be working part-time because their employer has reduced their hours, or because they cannot find a full-time job that matches their skills and experience. These individuals are counted as employed, but they are underemployed because they are not working as many hours as they would like.

Discouraged workers are those who have given up their job search because they believe that there are no jobs available for them. They may have been repeatedly rejected for jobs, or they may believe that their skills are outdated or irrelevant. These individuals are not counted as part of the labor force because they are not actively seeking work, but they represent a loss of potential productivity for the economy.

The U-6 unemployment rate provides a more comprehensive measure of labor underutilization by including marginally attached workers and those employed part-time for economic reasons. This rate consistently runs higher than the headline unemployment rate, reflecting the hidden challenges within the labor market. In times of economic distress, the gap between the U-3 and U-6 rates tends to widen, indicating a greater degree of labor underutilization.

The limitations of the headline unemployment rate have implications for policymakers and the public. Relying solely on this rate can lead to an incomplete understanding of the economic challenges facing the population. Policymakers may be less likely to implement policies aimed at addressing labor underutilization if they believe that the unemployment rate is low. The public may be less aware of the challenges faced by those struggling to find adequate employment.

A more comprehensive approach to measuring and addressing unemployment is needed. This approach should include consideration of a broader range of indicators, such as the U-6 unemployment rate, the labor force participation rate, and measures of wage growth and income inequality. It should also involve policies aimed at creating more full-time job opportunities, providing job training and skills development programs, and supporting workers facing barriers to employment.

Background Information:

The official unemployment rate is a key economic indicator that is closely watched by policymakers, economists, and the public. It is calculated monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) based on data collected from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of approximately 60,000 households. The CPS asks individuals about their employment status, work history, and job search activities.

The BLS defines unemployment as the state of being without a job, available to work, and actively seeking employment in the past four weeks. Individuals who meet these criteria are classified as unemployed. The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the number of unemployed individuals by the labor force, which is the sum of employed and unemployed individuals.

The unemployment rate is used to assess the health of the labor market and the overall economy. A low unemployment rate is generally seen as a sign of a strong economy, while a high unemployment rate is seen as a sign of a weak economy. However, the unemployment rate is not a perfect measure of economic well-being. It does not capture the experiences of those who are underemployed, marginally attached to the workforce, or discouraged workers.

The U-6 unemployment rate is a broader measure of labor underutilization that includes marginally attached workers and those employed part-time for economic reasons. This rate provides a more comprehensive picture of the challenges facing the labor market. In times of economic distress, the U-6 rate tends to be significantly higher than the headline unemployment rate.

The labor force participation rate is another important indicator of the health of the labor market. This rate measures the percentage of the population that is either employed or actively seeking employment. A high labor force participation rate is generally seen as a sign of a healthy economy, while a low labor force participation rate is seen as a sign of a weak economy.

The labor force participation rate has been declining in recent decades, due in part to demographic changes, such as the aging of the population. However, it has also been affected by economic factors, such as the decline in manufacturing jobs and the rise of automation. These factors have made it more difficult for some individuals to find employment, leading them to drop out of the labor force.

Expanded Context:

The issue of hidden unemployment is not unique to the United States. Many developed countries face similar challenges in accurately measuring and addressing labor underutilization. In some countries, the official unemployment rate may be even less representative of the true state of the labor market than in the United States.

For example, some countries have more restrictive definitions of unemployment, which may exclude certain categories of individuals who are struggling to find work. Other countries may have weaker social safety net programs, which may discourage individuals from actively seeking employment.

The rise of the gig economy has also contributed to the challenge of measuring unemployment. Many gig workers are classified as independent contractors, which means they are not eligible for unemployment insurance or other social safety net programs. This can make it difficult to track their employment status and to provide them with the support they need.

Addressing the issue of hidden unemployment requires a global effort. International organizations, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO), are working to develop more comprehensive measures of labor underutilization and to promote policies that support inclusive economic growth.

Policy Recommendations:

Addressing the issue of hidden unemployment requires a comprehensive set of policy interventions that address both the supply and demand sides of the labor market. Some potential policy recommendations include:

- Investing in Education and Training: Providing individuals with the skills and training they need to succeed in the modern economy is essential. This includes investing in education, vocational training, and apprenticeship programs.

- Expanding Access to Affordable Childcare: Lack of access to affordable childcare can be a major barrier to employment for many individuals, particularly women. Expanding access to affordable childcare can help more individuals enter and remain in the workforce.

- Improving Transportation Infrastructure: Lack of access to reliable transportation can also be a barrier to employment. Investing in transportation infrastructure can help connect individuals to job opportunities.

- Strengthening Social Safety Net Programs: Providing a strong social safety net can help individuals weather economic downturns and avoid falling into poverty. This includes expanding access to unemployment insurance, food assistance, and housing assistance.

- Raising the Minimum Wage: Raising the minimum wage can help reduce poverty and income inequality, and can also encourage more individuals to enter the workforce.

- Promoting Full Employment Policies: Policymakers should pursue policies that aim to achieve full employment, such as investing in infrastructure projects, supporting small businesses, and encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Combating Workplace Discrimination: Workplace discrimination can make it difficult for certain groups of individuals to find employment. Policymakers should enforce anti-discrimination laws and promote diversity and inclusion in the workplace.

By implementing these policies, policymakers can help reduce hidden unemployment and create a more inclusive and equitable economy that benefits all members of society.

Expert Opinions:

Economists and labor market analysts have long recognized the limitations of the headline unemployment rate and have advocated for a more comprehensive approach to measuring and addressing unemployment.

“The headline unemployment rate is a useful indicator, but it doesn’t tell the whole story,” said Heidi Shierholz, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute. “It’s important to look at a range of indicators to get a full picture of the labor market.”

“The U-6 unemployment rate is a more comprehensive measure of labor underutilization,” said Elise Gould, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute. “It includes marginally attached workers and those employed part-time for economic reasons.”

“Addressing the issue of hidden unemployment requires a multi-faceted approach,” said Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “It requires policies that address both the supply and demand sides of the labor market.”

Impact on Different Demographics:

The “hidden unemployment” phenomenon disproportionately affects certain demographic groups, exacerbating existing inequalities.

- Women: Women, particularly mothers, often face significant barriers to full-time employment due to childcare responsibilities. The lack of affordable and accessible childcare forces many women into part-time work or out of the labor force entirely, contributing to the ranks of the hidden unemployed.

- Minorities: Racial and ethnic minorities often experience higher rates of unemployment and underemployment due to systemic discrimination and lack of access to education and job training opportunities. This can lead to discouragement and withdrawal from the labor force, further masking their true employment status.

- Young Adults: Young adults, especially recent graduates, can struggle to find full-time employment that matches their skills and education. The rise of the gig economy and the prevalence of internships with little or no pay can also contribute to their underemployment.

- Older Workers: Older workers may face ageism and discrimination in the workplace, making it difficult for them to find new jobs after losing employment. They may also be forced into early retirement or settle for part-time work due to health concerns or family responsibilities.

- Individuals with Disabilities: Individuals with disabilities often face significant barriers to employment, including discrimination, lack of accessible workplaces, and inadequate job training. This can lead to high rates of unemployment and underemployment.

Understanding these demographic disparities is crucial for developing targeted policies and programs that address the specific challenges faced by each group.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ):

1. What is “hidden unemployment” and how does it differ from the official unemployment rate?

Hidden unemployment refers to the portion of the population struggling to find adequate work that is not accurately reflected in the official unemployment rate (U-3). This includes individuals who are marginally attached to the workforce (able and willing to work but haven’t actively searched in the past four weeks), those working part-time for economic reasons (wanting full-time work but unable to find it), and discouraged workers (who have given up actively searching for jobs). The official rate only counts those actively seeking employment, thus underrepresenting the true extent of labor underutilization.

2. What is the U-6 unemployment rate, and why is it a more comprehensive measure than the U-3 rate?

The U-6 unemployment rate is a broader measure of labor underutilization that includes not only the officially unemployed (U-3) but also marginally attached workers and those employed part-time for economic reasons. It provides a more comprehensive picture of the challenges within the labor market by accounting for individuals who are underemployed or have given up actively searching for work, offering a more realistic assessment of the labor force.

3. Why is it important to consider “hidden unemployment” when evaluating the health of the economy?

Considering hidden unemployment is crucial because the official unemployment rate alone can be misleading. A low U-3 rate may create a false sense of economic well-being while a significant portion of the population still struggles with joblessness or underemployment. Ignoring hidden unemployment can lead to inadequate policy responses and fail to address the real economic challenges faced by many Americans.

4. What are some factors contributing to “hidden unemployment” in the United States?

Several factors contribute to hidden unemployment, including technological advancements and automation reducing certain job types, the rise of the gig economy with its lack of benefits and stability, lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic causing job losses, skills gaps between job seekers and available positions, and discrimination in the workplace based on age, gender, race, or disability. The shortage of affordable childcare also keeps many women out of the workforce.

5. What policy changes could help reduce “hidden unemployment” and improve the labor market for all Americans?

To reduce hidden unemployment, policymakers should focus on investing in education and job training programs to bridge skills gaps, expanding access to affordable childcare to enable more parents to work, improving transportation infrastructure to connect individuals to job opportunities, strengthening social safety net programs to support those struggling to find work, raising the minimum wage to incentivize work and reduce poverty, promoting policies that encourage full employment, and actively combating workplace discrimination to ensure equal opportunities for all. A comprehensive approach is needed to create a more inclusive and equitable labor market.