Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s most successful pharaohs, endured a posthumous attack on her legacy in the form of statue desecration, now attributed not to spite, but to a pragmatic resource management strategy under her successor, Thutmose III, according to recent research published in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology.

The long-standing assumption that Thutmose III, Hatshepsut’s nephew and stepson, intentionally ordered the destruction of her images out of personal animosity and a desire to erase her from history, has been challenged by extensive archaeological analysis. Instead, the study posits that Thutmose III repurposed statues and building materials associated with Hatshepsut to legitimize his own reign and manage state resources effectively, a common practice in ancient Egypt.

“It’s been assumed for a long time that Thutmose III had some sort of personal grudge and was trying to erase Hatshepsut from history,” explains Dr. Betsy Bryan, Professor Emerita of Egyptian Art and Archaeology at Johns Hopkins University, who was not involved in the study. “But this new research suggests a more practical reason: resource management.”

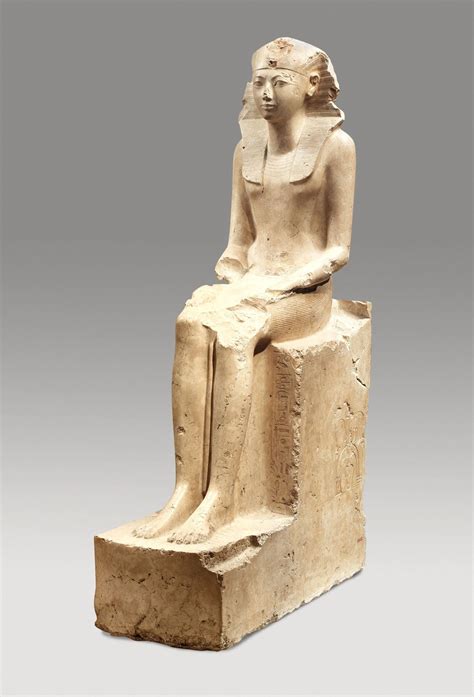

The research meticulously examined the damage patterns on Hatshepsut’s statues, coupled with the context of their re-use in subsequent construction projects. Researchers found that the destruction was often targeted at specific areas, such as the cartouches bearing Hatshepsut’s name, while the statues themselves were largely preserved. This selective defacement supports the idea that the primary goal was to remove Hatshepsut’s royal authority from the objects, rather than obliterate her memory entirely.

The study highlights the socio-economic pressures facing Thutmose III upon assuming sole rule. After Hatshepsut’s two-decade reign as pharaoh, Thutmose III inherited a kingdom with significant resource demands. Re-using existing materials, especially high-quality stone from Hatshepsut’s monumental projects, would have been a cost-effective and efficient way to undertake his own extensive building programs.

The practice of rulers appropriating and modifying the monuments of their predecessors was not uncommon in ancient Egypt. It served as a means of asserting their own legitimacy and demonstrating their power over the land. By inscribing his own name on Hatshepsut’s statues or incorporating them into his own temples, Thutmose III effectively declared himself the rightful heir and successor to the throne.

Dr. Bryan notes, “The Egyptians were very practical people. They wouldn’t just destroy perfectly good statues out of spite. Re-using them made perfect sense from an economic and logistical standpoint.”

Furthermore, the research underscores the complexity of ancient Egyptian history and the need to move beyond simplistic interpretations of events. The relationship between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III was undoubtedly complex, and their actions were likely motivated by a variety of factors, including political ambition, economic necessity, and ideological considerations.

The new evidence prompts a reevaluation of Hatshepsut’s legacy and the circumstances surrounding her reign. While the destruction of her images may seem like a deliberate attempt to erase her from history, the research suggests that it was more likely a calculated act of resource management and political maneuvering.

This interpretation does not diminish Hatshepsut’s significance as one of Egypt’s most remarkable rulers. Her successful reign, characterized by peace, prosperity, and ambitious building projects, left an indelible mark on Egyptian history. Understanding the motivations behind the subsequent modifications to her monuments provides valuable insights into the political and economic realities of ancient Egypt.

The ongoing research into Hatshepsut’s reign and the actions of Thutmose III continues to unveil new aspects of this fascinating period in Egyptian history, pushing historians to continuously re-evaluate established narratives and explore the complexities of power, legacy, and resource management in the ancient world.

In-depth Analysis

The study challenging the long-held belief regarding the defacement of Hatshepsut’s statues presents a compelling case for reinterpreting historical events through the lens of resource management and political pragmatism. To fully grasp the significance of this new perspective, we must delve deeper into the historical context, the archaeological evidence, and the implications of this revised understanding.

Historical Context: Hatshepsut’s Reign and Thutmose III’s Ascension

Hatshepsut’s reign (c. 1479-1458 BC) was a unique period in Egyptian history. As a female pharaoh, she defied traditional gender roles and successfully ruled Egypt for over two decades. She initially served as regent for her stepson, Thutmose III, who was too young to rule when his father, Thutmose II, died. However, Hatshepsut gradually assumed the full authority of pharaoh, adopting royal titles and regalia.

During her reign, Hatshepsut focused on domestic development and trade, rather than military expansion. She commissioned numerous building projects, including the magnificent temple complex at Deir el-Bahri, which served as a mortuary temple and a testament to her divine legitimacy. Her reign was marked by peace and prosperity, and she is remembered as one of Egypt’s most successful rulers.

Thutmose III, upon assuming sole rule after Hatshepsut’s death, embarked on a series of military campaigns that expanded Egypt’s empire to its greatest extent. He is often referred to as the “Napoleon of Egypt” due to his military prowess. Thutmose III also undertook extensive building projects of his own, including additions to the Karnak Temple complex.

Archaeological Evidence: Examining the Damage Patterns

The new research focuses on a detailed analysis of the damage patterns on Hatshepsut’s statues and monuments. Researchers examined the types of damage, the locations of the damage, and the context in which the damaged objects were found.

One key finding is that the damage was often selective. Cartouches containing Hatshepsut’s name were frequently defaced, while the statues themselves were largely preserved. This suggests that the primary goal was to remove Hatshepsut’s royal authority from the objects, rather than obliterate her memory entirely.

In some cases, Hatshepsut’s statues were incorporated into Thutmose III’s own building projects. For example, statues of Hatshepsut were found reused in the construction of Thutmose III’s temple at Deir el-Bahri. By inscribing his own name on these statues, Thutmose III effectively claimed them as his own.

The research also considers the logistical challenges of destroying large stone statues. Completely obliterating a statue would have been a time-consuming and labor-intensive task. It would have been much more efficient to simply remove the cartouches and repurpose the statue for another use.

Resource Management and Political Pragmatism

The new interpretation emphasizes the role of resource management and political pragmatism in Thutmose III’s actions. After Hatshepsut’s reign, Thutmose III inherited a kingdom with significant resource demands. His military campaigns required vast amounts of supplies and manpower, and his building projects required large quantities of stone and other materials.

Re-using existing materials, especially high-quality stone from Hatshepsut’s monumental projects, would have been a cost-effective and efficient way to undertake his own building programs. This would have saved time, labor, and resources.

In addition to resource management, Thutmose III’s actions may have been motivated by political considerations. By appropriating Hatshepsut’s monuments and inscribing his own name on them, he asserted his own legitimacy as the rightful ruler of Egypt. This would have helped to consolidate his power and prevent any potential challenges to his authority.

Challenging the Traditional Interpretation

The traditional interpretation of the defacement of Hatshepsut’s statues is that it was a deliberate attempt to erase her from history out of personal animosity. This interpretation is based on the assumption that Thutmose III resented Hatshepsut for usurping his throne and that he sought to eliminate her memory from Egyptian history.

However, the new research challenges this interpretation by providing evidence that the damage was selective, that statues were often reused, and that resource management and political pragmatism played a significant role.

While it is possible that Thutmose III harbored some resentment towards Hatshepsut, the new research suggests that his actions were primarily motivated by practical considerations. He was a pragmatic ruler who was focused on consolidating his power and managing the resources of his kingdom effectively.

Implications for Understanding Ancient Egyptian History

The new interpretation of the defacement of Hatshepsut’s statues has significant implications for our understanding of ancient Egyptian history. It highlights the importance of considering the economic and political context when interpreting historical events. It also underscores the complexity of ancient Egyptian society and the need to move beyond simplistic interpretations of events.

The research also emphasizes the importance of archaeological evidence in reconstructing the past. By carefully examining the damage patterns on Hatshepsut’s statues, researchers were able to gain new insights into the motivations behind Thutmose III’s actions.

The Role of Propaganda and Legitimacy

In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was not only a political ruler but also a divine figure. The pharaoh’s legitimacy was crucial for maintaining social order and ensuring the stability of the kingdom. Propaganda played a key role in establishing and maintaining the pharaoh’s legitimacy.

Hatshepsut faced a unique challenge in establishing her legitimacy as a female pharaoh. She employed various strategies to overcome this challenge, including portraying herself as a male ruler in her statues and emphasizing her divine birth.

Thutmose III also used propaganda to legitimize his rule. His military campaigns and building projects were portrayed as evidence of his strength and divine favor. By appropriating Hatshepsut’s monuments, he further asserted his legitimacy as the rightful successor to the throne.

Comparative Analysis: Parallels in Other Ancient Societies

The practice of rulers appropriating and modifying the monuments of their predecessors was not unique to ancient Egypt. Similar practices have been observed in other ancient societies, such as Rome and Mesopotamia.

In Rome, emperors often built upon or modified the monuments of their predecessors. This was a way of demonstrating their own power and legitimacy and of associating themselves with the achievements of their predecessors.

In Mesopotamia, rulers often destroyed or defaced the monuments of their enemies as a way of asserting their dominance. They also built new monuments to commemorate their own victories and achievements.

These comparative examples illustrate that the appropriation and modification of monuments was a common practice in ancient societies. It was a way of asserting power, legitimizing rule, and managing resources.

Ongoing Research and Future Directions

The research into Hatshepsut’s reign and the actions of Thutmose III is ongoing. New archaeological discoveries and analytical techniques continue to provide new insights into this fascinating period in Egyptian history.

Future research may focus on examining the distribution of Hatshepsut’s statues and monuments throughout Egypt. This would help to determine the extent of the damage and the patterns of reuse.

Researchers may also use advanced imaging techniques to analyze the damage patterns in greater detail. This could reveal new information about the tools and techniques used to deface the statues.

Finally, further research may focus on the social and political context of the defacement of Hatshepsut’s statues. This could help to shed light on the motivations behind Thutmose III’s actions and the impact of these actions on Egyptian society.

The Enduring Legacy of Hatshepsut

Despite the modifications to her monuments, Hatshepsut’s legacy endures as one of Egypt’s most remarkable rulers. Her successful reign, characterized by peace, prosperity, and ambitious building projects, left an indelible mark on Egyptian history.

Hatshepsut’s temple complex at Deir el-Bahri remains one of the most impressive architectural achievements of ancient Egypt. Her statues and monuments, even those that were modified, continue to inspire awe and admiration.

Hatshepsut’s story is a reminder of the power of women in ancient history and the challenges they faced in asserting their authority. Her reign challenges traditional gender roles and demonstrates the potential for women to achieve greatness in any field.

The ongoing research into Hatshepsut’s reign and the actions of Thutmose III provides valuable insights into the complexities of ancient Egyptian history. It reminds us that history is not a static narrative but a dynamic and evolving field of study. By continuing to explore the past, we can gain a deeper understanding of the present and the future.

Conclusion

The notion that Thutmose III systematically eradicated Hatshepsut’s memory due to personal animosity has been challenged by recent research. This research, published in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, suggests that the defacement and repurposing of Hatshepsut’s statues were driven primarily by resource management and political pragmatism. By analyzing the damage patterns on Hatshepsut’s statues and considering the economic and political context of the time, researchers have provided a more nuanced understanding of Thutmose III’s actions. This new perspective does not diminish Hatshepsut’s significance as one of Egypt’s most successful pharaohs but rather offers a more complex and realistic view of the power dynamics in ancient Egypt. It is a testament to the evolving nature of historical interpretation and the importance of continuously reevaluating established narratives in light of new evidence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Why were Hatshepsut’s statues damaged?

The prevailing historical narrative suggested that Thutmose III ordered the destruction of Hatshepsut’s statues out of spite and a desire to erase her from history. However, recent research indicates that the damage was likely due to a combination of factors, including resource management and political pragmatism. Thutmose III repurposed Hatshepsut’s statues and building materials to legitimize his own reign and efficiently manage state resources. The damage was often selective, targeting cartouches bearing Hatshepsut’s name rather than destroying the statues entirely.

2. What evidence supports the new interpretation of statue desecration?

The new interpretation is supported by a detailed analysis of the damage patterns on Hatshepsut’s statues. Researchers found that the damage was often selective, targeting specific areas such as the cartouches bearing Hatshepsut’s name, while the statues themselves were largely preserved. Additionally, many of Hatshepsut’s statues were found reused in Thutmose III’s own building projects, suggesting that the primary goal was to remove Hatshepsut’s royal authority from the objects, rather than obliterate her memory entirely.

3. Was it common for rulers in ancient Egypt to repurpose monuments?

Yes, it was a relatively common practice for rulers in ancient Egypt to appropriate and modify the monuments of their predecessors. This served as a means of asserting their own legitimacy and demonstrating their power over the land. By inscribing their own name on existing structures or incorporating them into their own temples, rulers could declare themselves the rightful heir and successor to the throne. Repurposing also allowed efficient resource management by utilizing existing building materials.

4. Did Thutmose III resent Hatshepsut?

While it is possible that Thutmose III harbored some resentment towards Hatshepsut for ruling as pharaoh during his minority, the new research suggests that his actions were primarily motivated by practical considerations. He was a pragmatic ruler focused on consolidating his power and managing the resources of his kingdom effectively. The debate continues on the extent of personal animosity versus political and economic strategies.

5. How does this new interpretation change our understanding of Hatshepsut’s legacy?

This new interpretation does not diminish Hatshepsut’s significance as one of Egypt’s most remarkable rulers. Her successful reign, characterized by peace, prosperity, and ambitious building projects, left an indelible mark on Egyptian history. Instead, it provides a more nuanced and complex understanding of the political and economic realities of ancient Egypt, highlighting the importance of resource management and political maneuvering in shaping historical events. This invites historians and researchers to re-evaluate other established narratives and continuously explore the complexities of power, legacy, and resource management in the ancient world.

6. What motivated Hatshepsut to become Pharaoh?

Hatshepsut’s motivations for assuming the role of pharaoh are complex and debated among historians. After the death of her husband, Thutmose II, his son Thutmose III was too young to rule. Hatshepsut initially acted as regent, but over time, she gradually consolidated power and adopted the full titles and regalia of a pharaoh. Several factors likely contributed to this decision. First, as a royal woman with strong lineage, she may have felt a responsibility to ensure the stability of Egypt. Second, she likely had ambitions for power and a desire to leave her own mark on history. Third, she portrayed herself as divinely ordained to rule, bolstering her legitimacy in a society that traditionally favored male rulers.

7. What were the defining characteristics of Hatshepsut’s reign?

Hatshepsut’s reign was characterized by peace, prosperity, and ambitious building projects. Unlike many pharaohs, she focused on domestic development and trade rather than military expansion. She commissioned numerous impressive structures, including her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, which is considered one of the architectural masterpieces of ancient Egypt. Her reign saw increased trade and diplomatic relations, contributing to Egypt’s economic strength. Hatshepsut also emphasized her divine connection to legitimize her rule, often depicting herself as a female version of a male pharaoh in her statues and inscriptions.

8. How did Hatshepsut legitimize her rule as a female Pharaoh?

Hatshepsut employed various strategies to legitimize her rule as a female pharaoh in a traditionally male-dominated society. She emphasized her royal lineage, claiming direct descent from the god Amun. She often depicted herself in statues and inscriptions with male pharaonic attributes, such as a false beard and traditional pharaoh’s clothing, to present herself as a strong and capable ruler. Additionally, she commissioned extensive building projects and promoted trade, demonstrating her ability to bring prosperity and stability to Egypt. Her propaganda also focused on the divine support for her reign, reinforcing her legitimacy in the eyes of her people.

9. What impact did Hatshepsut’s building projects have on Egypt?

Hatshepsut’s extensive building projects had a significant impact on Egypt. They created jobs for artisans and laborers, stimulating the economy. These projects also showcased Egypt’s wealth and power, enhancing its international prestige. Her most famous building project, the mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, became a symbol of her reign and demonstrated her artistic vision. These projects also served a religious purpose, honoring the gods and reinforcing Hatshepsut’s connection to the divine. Overall, her building projects contributed to the cultural, economic, and religious life of Egypt during her rule.

10. What is the significance of the Deir el-Bahri temple?

The Deir el-Bahri temple, also known as Djeser-Djeseru (“Holy of Holies”), is Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple and stands as one of the most significant architectural achievements of ancient Egypt. It showcases innovative architectural design, blending seamlessly with the natural landscape. The temple was dedicated to Amun-Re, Hatshepsut’s patron deity, and served as a place for her posthumous worship and as a symbol of her divine authority. It is adorned with detailed reliefs and inscriptions documenting her reign, her divine birth, and her accomplishments. The temple also served as a venue for religious festivals and ceremonies, underscoring Hatshepsut’s role as a religious leader. Its grandeur and artistic sophistication have made it a lasting testament to her reign and a major source of insight into ancient Egyptian culture and beliefs.